Basically, my question is the title. If a black hole crosses the Roche limit of another black hole, what happens?

For a hypothetical example, let’s say you have a two black holes: one at 5 solar masses and one at 300 solar masses. If the smaller black hole crosses the Roche limit of the larger what happens? Does they simply merge? Would the event horizon of one or both black hole’s be geometrically distorted in some way or retain their spherical shape?

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binary_black_hole

The two event horizons stretch out toward each other, form some interesting shapes, connect into a cylindrical bridge shape, and then the combined horizon smooths itself out while emitting large amounts of gravitational radiation.

For “realistic” scenarios where these black holes start out in a binary elliptical orbit, the final ringdown phase concludes very rapidly. Gravitational waves are emitted continuously during the inspiral phase, in a manner analogous to how an electron in a circular orbit emits electromagnetic radiation.

The event horizon itself is a mathematical boundary of neither matter nor energy, so it does not appear to slow down or stop from time dilation. (From the perspective of a distant outside observer).

The no-hair theorem applies to stationary black hole solutions. That is, after event horizon ring down is completed.

Editing myself to directly answer the information question:

If you observe an event horizon on a complex distorted bridge shape, you can deduce information about the original merger partners. This is not a violation of any principle, because the famous no hair theorem does not apply in this situation.

The complex shape condition is not stable, and it relaxes to a “simple” shape that provides no information about the individual merger partners. This process completes in finite time, and is usually quite fast.

During this process, undulations and ripples in the shape of the event horizon result in emitted gravitational waves. Presumably, these gravitational waves contain the last information you can possibly get about the original merger partners.

Second edit: I am not a physicist, but I can read Wikipedia. Feel free to correct me.

No, not just presumably. LIGO picks up and measures black hole mergers semi-regularly. They’re just loud (in gravitational waves) and very easy to interpret.

I don’t think anything except merging would happen.

The Roche limit is for things held together by gravity and that can escape from said gravity. It’s basically the stronger external gravity winning out over internal gravity.

The problem is nothing can escape the singularity so how could it break apart?

The roche limit usually just refers to the effects of gravity upon a smaller object, and how it can potentially break it up in orbit. For black holes it’s not really the same effect. The only thing that does affect black holes is the moment their event horizons touch, which then drags the smaller black hole into an inevitable merger of the two.

If general relativity is exactly correct (in that there lies a point like singularity at the center of a black hole), then the Roche limit of black holes would be zero. Why would it be zero? Because the singularity isn’t a solid sphere. It’s a point of infinite density with a radius of 0. Basically, what this means is that the concept of a Roche limit ceases to exist here.

However, we know that general relativity doesn’t correctly describe reality at the quantum scale. Classical physics (which general relativity is based upon) contradicts quantum physics in many ways. Singularities work at the quantum scale. Singularities of black holes also only interact through gravity. Because gravity is incredibly weak, we have not been able to experiment with it at the quantum scale. So we don’t know how gravity works at the quantum scale yet.

Therefore, we don’t even know if singularities exist inside black holes. Basically, we have no clue about what happens inside black holes, how general relativity and gravity works at small scales and what exactly happens during a black hole merger.

We could answer the above questions after we understand quantum gravity.

I asked this some months ago. The consensus seemed to be the they merge and become one. But I can’t get passed the feeling that the two centres of mass becoming one and the same gives us some sort of info about what happens behind the combined event horizon, which seems wrong. So if that’s not what happens then perhaps the two black holes only appear merged, but actually they’re just very close, and from our view they’re perpetually falling toward each other slowed by relativistic effects?

I’d love to watch an actual scientist tackle this question. Without an answer from a professional there isn’t an answer.

FWIW the Wikipedia page on the first detection a few times quotes the research papers that they do “merge”. A process whose completeness seems emphasised by the subsequently detected ripples that decay to nothing which they call the “ringdown”.

But yes, explanation by a professional would be fantastic

That’s pretty cool.

Supposedly tomorrow all the planets are going to line up at night. If you enjoy science and stuff look up for that.

Very good. The problem is that singularities are quantum objects. Quantum physics works nothing like classical physics.

For example, in the case of perpetually falling singularities, would they just quantum tunnel into each other? Or would singularities even exist? According to general relativity, singularities are a sphere that never stops being compressed due to its own gravity. What happens when this sphere hits a diameter smaller than Plank’s length? Does the universe take a screenshot? The point is, we have absolutely no clue about what’s happening here.

To understand the above, we would first need to understand how gravity works at the quantum level, which we don’t. Why? Gravity is incredibly weak. Studying it is thus, very hard.

One could say the same for the mass of each of the black holes as well from the start of their collapse, and anything else they’ve ingested. They are still falling into their singularity point, forever.

I was curious about the shape of the event horizon part of the question. I don’t know the answer, but this paper makes it clear that a lot of complicated maths is involved, and provides some diagrams that can give you a rough idea of the kind of shapes that might be involved, such as in figure 3 on page 6.

The singularity is like a state of matter and time merged into one. So the black hole is not an object or baryonic matter. The observable effects are limited to stuff in orbit and the bending of time. That stuff would be going wild, but in terms of the singularity itself, it is more like two enormous gravity wells of infinite depth in time. The walls of that well can be moved around a bit but there is no way to make the well anything but larger. The one exception being Hawking radiation. That is a hole in reality, not an object… probably wrong, but that is how I understand it.

Commenting here to return if someone answers

There is probably a way to bookmark it in the app you use.

I tend to not use apps since there’s a perfectly fucking fine working web browser that does the same shit as an app, but also happens to not track my telemetry including the frequency of my shits daily that most apps do nowadays.

That browser also has a bookmark feature.

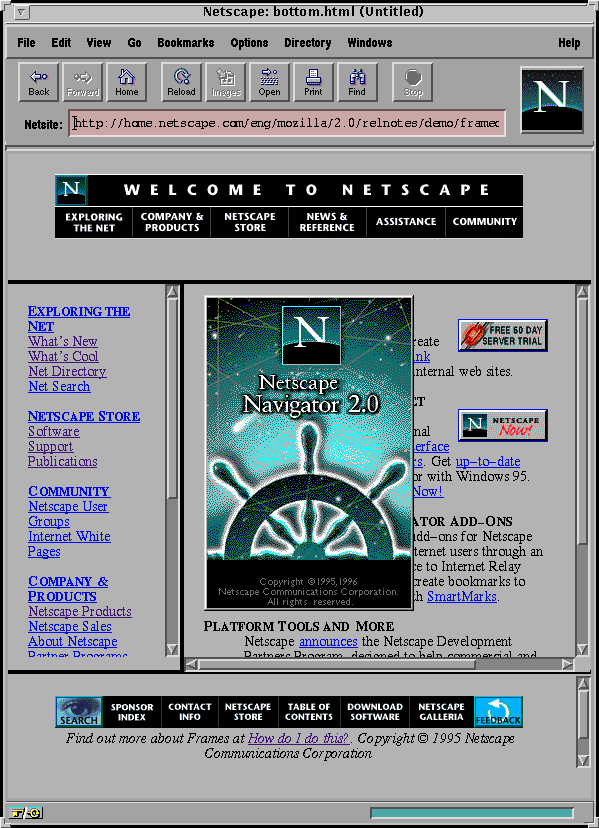

Not mine, I use Netscape Navigator in a Windows 95 VM within Ubuntu running on a Nintendo Switch.

Lynx running on Linux From Scratch with a custom hardened kernel and only the bare minimum number of packages for a functioning tty would be a better choice, but who am I to judge?

I want to try this in a qube now.

That is some good taste, mate.